Michael Halberstam’s ‘The Wanting of Levine’: An Uncanny 1970s Political Novel Worthy of Rejuvenation

Any serious novelist worth their salt fantasizes that their work will endure beyond their lifetime. As both an earnest practitioner of the novelist’s art and a lifetime student of classic literature, I am always heartened when I learn about a novel written decades ago, long buried from public view, that suddenly pops into the public consciousness offering remarkably pertinent moral and psychological insights that eerily reflect contemporary events and concerns.

There is no easy explanation for a novel’s comeback. If one looks closely at the historical record of once popular novels, as measured by the bestseller lists, one sees a startling lack of endurance. They enter with a shout and, for the most part, exit in barely a whisper. The trigger that signals a novel’s rejuvenation is mysterious, magical and unpredictable. I am reminded of Henri Beyle, a Frenchman writing under the nom de plume of Stendhal who dedicated his novel The Red and the Black to the ‘happy few’ as if divining in advance the lack of contemporary readers of this novel which deals with the universal themes of the addictive and often destructive nature of ambition and love. His not too subtle dedication was correct. What he could not predict was the endurance of his novel, which has become one of the great classics of French literature.

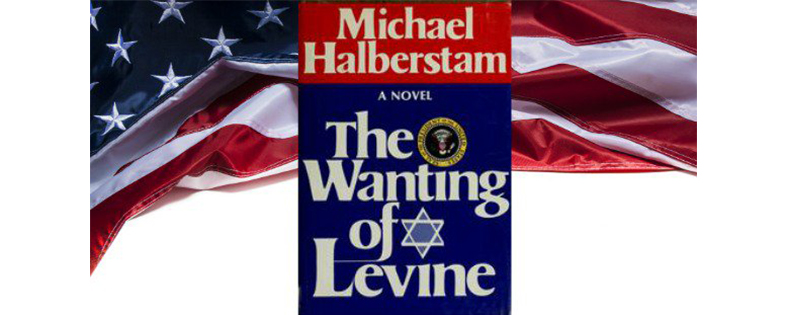

There are many such examples scattered throughout the world of literature and my attention was captured recently by Michael Halberstam’s sensationally revealing and brilliant political novel The Wanting of Levine, published in 1978, that centers around a real estate mogul, A.L. Levine, who has made his fame and fortune in land and property. Although he has never before run for office and has no political background, he decides to run for President on the Democratic ticket and is eventually elected. Upon his election, he tellingly comments ‘Politics is a kind of entertainment, and people want novelty in politics like they want it in anything else. Simultaneously, they want continuity.’ He is a married adulterer with a radical son and his past and present are meticulously autopsied. The novel was modestly received and quickly passed into oblivion. I came across a reference to it recently in the New York Sun, one of the many habitual digital outlets I read to keep abreast of the current ten ring political circus now performing in Washington.

Michael was a casual friend of mine in Washington. He was a Doctor with a large practice among the Washington political and social elite and we met socially during the years when my wife was editor-in-chief and owner with my son David of the Washington Dossier, a society magazine that covered the nation’s capital.

It was during the seventies and eighties and coincided with the beginning of my full-time novel-writing career. I would accompany my wife on her coverage rounds, cocktail parties, dinners and events in venues at embassies, private residences and ballrooms providing numerous interactions with diplomats, politicians, lobbyists, cabinet ministers, and high-level policy makers from every branch of government, and a vast array of experts, and professional and amateur gurus of every stripe and nationality. This milieu was peopled with a heady mix of power brokers and a priceless secretive social interaction for a disguised novelist whose antenna was forever circling the atmosphere for ideas, insights, information, plot lines, character studies, and mining scenarios that would one day surface as inspiration for numerous Washington-based novels.

I would calculate that more than three quarters of my fifty novels owe their germination to these social events and I would bet the barn that Michael Halberstam, who traveled in these circles as well, was soaking up material for his own secretive ambition to become a novelist, gaining insight and ideas as well from his medical practice among the high and mighty of the Washington crowd. I enjoyed engaging with him, not knowing that we were probably doppelgangers on the same hunt for story material. It was beyond horrible when on returning from one of his social adventures his life was cut short by a man who shot him dead when Michael discovered him burgling his home.

The novel begins with a nod toward Dickens. ‘It was the worst of times, the worst of times, the worst of times. Everybody thought so, though no one exactly knew why.’ The story resonates with profoundly alarming accuracy and withering insight into the often absurd machinations of the American political process and strips bare the motives and weirdness of the characters who play in that arena. What makes the novel especially prescient is the way in which he touches most of the bases of political chicanery within the framework of a kind of dystopian fantasy. He lays bare all of the fault lines that have brought the country to what for him was its dire straits. States were no longer united. Each one was an enclave. Every aspect of American society eating away at our democracy: race, crime, poverty, inequality, discrimination, the whole menu of deadly sins gets Halberstam’s attention. Politics is all window dressing, media promotion, dissimulation and media manipulation, nothing escapes Halberstam’s scalpel.

As one of the characters comments, ‘I dislike the whole nasty bunch…Politicians heaping up their own sand castles at the people’s expense and the press trying to get a name for itself by knocking the sand castles down. Revolting people. Non producers…’

If ever a novel cries out for rejuvenation, this one does, especially now. It is perhaps one of the best Washington novels I have ever come across and I hope The Wanting of Levine finds its way to popularity with the same degree of enthusiasm as the revival of The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood.

In the tragic demise of my casual friend Michael Halberstam, we lost the mind, heart and wisdom of someone who had the brilliance and talent to create stories of masterly fiction. I cry for his loss.

Originally published on Interesting Literature here.