Real Estate and Rubble: When Marriages Go Awry

As her lawyers tell it, the man suspected of blowing up the house was the personification of evil. The ex-wife hid from the Nazis as a child; he drew swastikas all around their house. Their children tried to call him, but he sputtered curses and hung up the phone: he accused them of siding with their mother. Finally, the authorities suspect, he destroyed the house so she wouldn’t get it.

His former lawyer tells a different version: that he was hounded by aggressive lawyers who stripped him of his dignity and everything he owned, taking his beloved house when he was too depressed to defend himself.

The battle between Nicholas Bartha, 66, an Upper East Side doctor, and his ex-wife, Cordula Hahn, 64, weaves through pages and pages of court documents, but in New York, lawyers say, while blowing up a building is extreme, vindictiveness is not unusual. Divorce lawyers said they had seen pets killed and wives given theater tickets so their husbands could put their possessions on the street.

Some say such spiraling levels of anger, rage and eventually violence are a function of New York’s cumbersome divorce laws, which require one spouse to find fault with the other and thus encourage lawyers to keep the fight going as long as possible, spousal tensions rising all along. Experts noted that while the Barthas had been fighting for five years, even after their divorce became final, some epic New York divorce wars have gone on way, way longer.

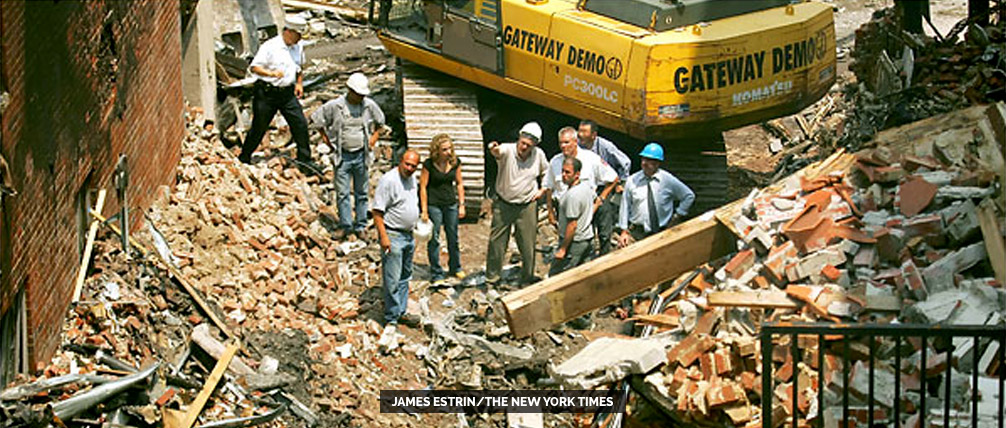

Homes are valuable possessions, and one of the most sentimental, so they are always a flashpoint. But in New York City, more than almost anywhere else, real estate is the new wealth, and the escalation of prices — the demolished home rose in value from $395,000 in 1980 to more than $6 million today — has raised the stakes in the brutal parlor game of divorce.

Dr. Bartha vowed he would turn his ex-wife from “gold digger” into “ash and rubbish digger.” But New York’s rich supply of wealthy spouses and messy divorces have spawned many battle cries, from the ghoulish to the girlish, like Ivana Trump’s “Don’t get mad, get everything!”

“It’s not uncommon for people to say ‘over my dead body,’ ” Susan M. Moss, a Manhattan matrimonial lawyer, said yesterday. “Usually, calm and reason take over, and the spouse realizes this isn’t the end of the world and life will go on.”

If Las Vegas is the capital of instant divorce, New York City is the worldwide capital of unfathomably big awards and ferocious litigation. Think of Donald and Ivana Trump, Rudolph W. Giuliani and Donna Hanover, Jocelyne and Alec Wildenstein, Ronald O. Perelman and Patricia Duff.

But even anonymous New Yorkers can find themselves in the midst of a titanic struggle.

Raoul Felder, who represented Mr. Giuliani in his divorce from Ms. Hanover, said he had seen works of art and record collections slashed by angry spouses, a puppy put in a microwave and a cat in a washing machine. “The puppy died, the cat lived,” he said.

Ms. Moss recalled an opposing lawyer calling her to say that her client was standing on her husband’s driveway, about to take a sledgehammer to his Porsche.

Ms. Moss called her client’s cellphone and managed to calm her down. “I said, ‘It’s only a Porsche,’ ” she recalled. “ ‘If you’re calm and cool and collected, we’ll get you enough money to buy your own Porsche.’ ”

During the course of her 26-year marriage to Dr. Bartha, Ms Hahn had seen her husband change from a dashing young medical student into a withdrawn, embittered and verbally abusive man, said her lawyer, Donna Bennick. When swastikas, clumsily drawn on newspaper articles, began appearing in kitchen cabinets and counters in their town house in the summer of 2001, her lawyer said, Ms. Hahn knew she had to leave.

The swastikas were more than symbols to Ms. Hahn. Some of her relatives died in Auschwitz, her lawyer said, and as a toddler, she was hidden from the Nazis with her parents and siblings by members of the Dutch underground.

“The swastikas were very traumatic to her,” Ms. Bennick said. “She came to see me and we made a safety plan for her exit.”

Ms. Hahn left Dr. Bartha and the town house that had become his central obsession in October 2001. Her daughters, Serena and Johanna, left with her, weary of their strict, hypercritical father who broke long bouts of stony silence only to fire insults their way, Ms. Bennick said.

Afterward, when Serena or Johanna tried to phone or visit their father, he burst into angry tirades, Ms. Bennick said. Serena Bartha is a chef in New York, and Johanna Bartha a designer at Nike in the Netherlands, but Dr. Bartha dismissed them as disappointments. His wife was “supposed to educate her children,” he wrote in an e-mail message just before the explosion, “and I do not think that a cook and a seamstress is a very good result.”

Neither daughter had had contact with their father in two and a half years, Ms. Bennick said. Serena was seen leaving the hospital where her father was being treated yesterday evening.

Yet others said that Dr. Bartha could be a sympathetic figure.

Mark Baum, a real estate broker who helped rent the town house’s apartment, said Dr. Bartha was “desperately hurt” by the split, especially his daughters’ decision to leave with their mother. As for the swastikas, Mr. Baum was mystified. Dr. Bartha called him every Rosh Hashana to wish him “a happy and a healthy” year, he said. “He was a little quirky, but he was always kind.”

Dr. Bartha’s former lawyer, Ira E. Garr, said Ms. Hahn won her legal battle to get control of the house when Dr. Bartha was too depressed to try to fight back.

Real estate records show that the house was bought by his parents, John and Ethel, in 1980. Dr. Bartha’s father gave him a half-interest, and then his mother, when she died, left a quarter interest to Dr. Bartha and a quarter interest to his daughters.

In the original divorce proceeding, Mr. Garr successfully argued that the house was Dr. Bartha’s separate property — not marital property. The judge agreed. On appeal, the house was found to be marital property, and the appellate court sent the case back to be retried on financial issues.

Mr. Garr said he wanted to appeal further, but Dr. Bartha stopped returning phone calls or answering letters. “I didn’t get permission from him to do anything; he didn’t respond,” Mr. Garr said.

Frustrated and owed money for legal fees, Mr. Garr said, he withdrew from the case. He said he had not spoken to the doctor for some time and speculated that he might have been heartbroken and not acting out of greed. After she won the appeal, Mr. Garr said, Ms. Bartha won a judgment against her ex-husband by default because he did not show up for a hearing.

Mr. Garr did not blame the judge for issuing the default judgment, saying, “The judge is not a mind reader. Nobody’s got a crystal ball saying he’s depressed. Maybe he’s on vacation in Hawaii. There’s just no way” for the judge to know.

New York is the only state that has not adopted no-fault divorce, and experts said that situation encouraged spouses to exaggerate claims of mistreatment. For lawyers paid by the hour, there is little incentive to keep the rhetoric down, because the more tied-up a divorce gets, the higher their fees.

In February, New York State’s chief judge, Judith S. Kaye, called on the Legislature to follow the recommendation of a matrimonial commission she had appointed that said that New York should join all the other states in adopting no-fault divorce.

The commission said that New York had put up some of the strictest barriers in the nation to divorce, by requiring one party to prove cruel and inhuman treatment, adultery, or abandonment for a year.

“Divorce takes much too long and costs much too much,” Judge Kaye said in her annual address on the state of the judiciary last February. Often, lawyers admitted, some lawyers ratchet up the rhetoric in an effort to resolve cases. In papers that Ms. Hahn filed in March, seeking to evict her husband from the house so it could be sold to satisfy her judgment, her lawyers listed legal fees that they hoped to collect, including nearly $20,000 for Ms. Bennick and another $23,000 for a second lawyer, Polly N. Passonneau.

Stanford Lotwin, who represented Donald Trump in both of his divorces, said that on a scale of 1 to 10, the divorce and financial battle between Dr. Bartha and Ms. Hahn was “an 11.”

Warren Adler, author of “The War of the Roses,” who heard Dr. Bartha’s town house explode yesterday from his own apartment on East 56th Street, also weighed in.

His fictional book, (he has been married for 50 years), ends with a divorcing couple dying in the wreckage of the house that both of them refused to give up. “I wrote that book 25 years ago, but wherever I travel, people will say to me, ‘You stole my divorce,’ ” to tell the tale, Mr. Adler said yesterday.

“This is what happens when possessions take the place of emotions. I know I got it right, and this is just one other vindication.”

View original article: Real Estate and Rubble: When Marriages Go Awry